As a writer, I love giving readers something they didn’t expect. When plotting a murder mystery, I meticulously plant clues, red herrings, and unexpected connections, ensuring readers will turn the pages, eager for what’s next. The writer's mind is a playground. It’s the world as we know it—the familiar, the structured, and the understood. Readers are conditioned for the norm. But when a writer disrupts the mundane, offering a twist, it intrigues and refreshes.

We’re curious beings. We crave learning and understanding. We seek order. Flipping gender roles or challenging leadership expectations is a surefire way to shake things up and offer a new perspective.

Last year, I wrote a scene I initially thought was humorous: an 1800s heroine, desperate to become a physician, disguises herself as a man to attend medical lectures. At the time, women were barred from pursuing careers as scientists or physicians, often resorting to extraordinary measures to follow their passions. In the scene, Scarlett, the determined heroine, is on the verge of being discovered. Her nemesis, an immigrant physician named Steven, steps in to save her by pretending she’s his male cousin. This clever ruse spares Scarlett from scandal but forces her to blend in with the men—including accompanying them to a brothel. Turning the tables, Scarlett ends up saving Steven. While he’s incapacitated during a narcoleptic episode, she kisses him, adding what I thought was a layer of comedic drama to the brothel scene.

Here’s the rub: that kiss happened without his consent. He was barely conscious. It doesn’t matter if it was funny, if readers were in on the joke, or if it showcased her autonomy. By giving her this power, I stripped his from him.

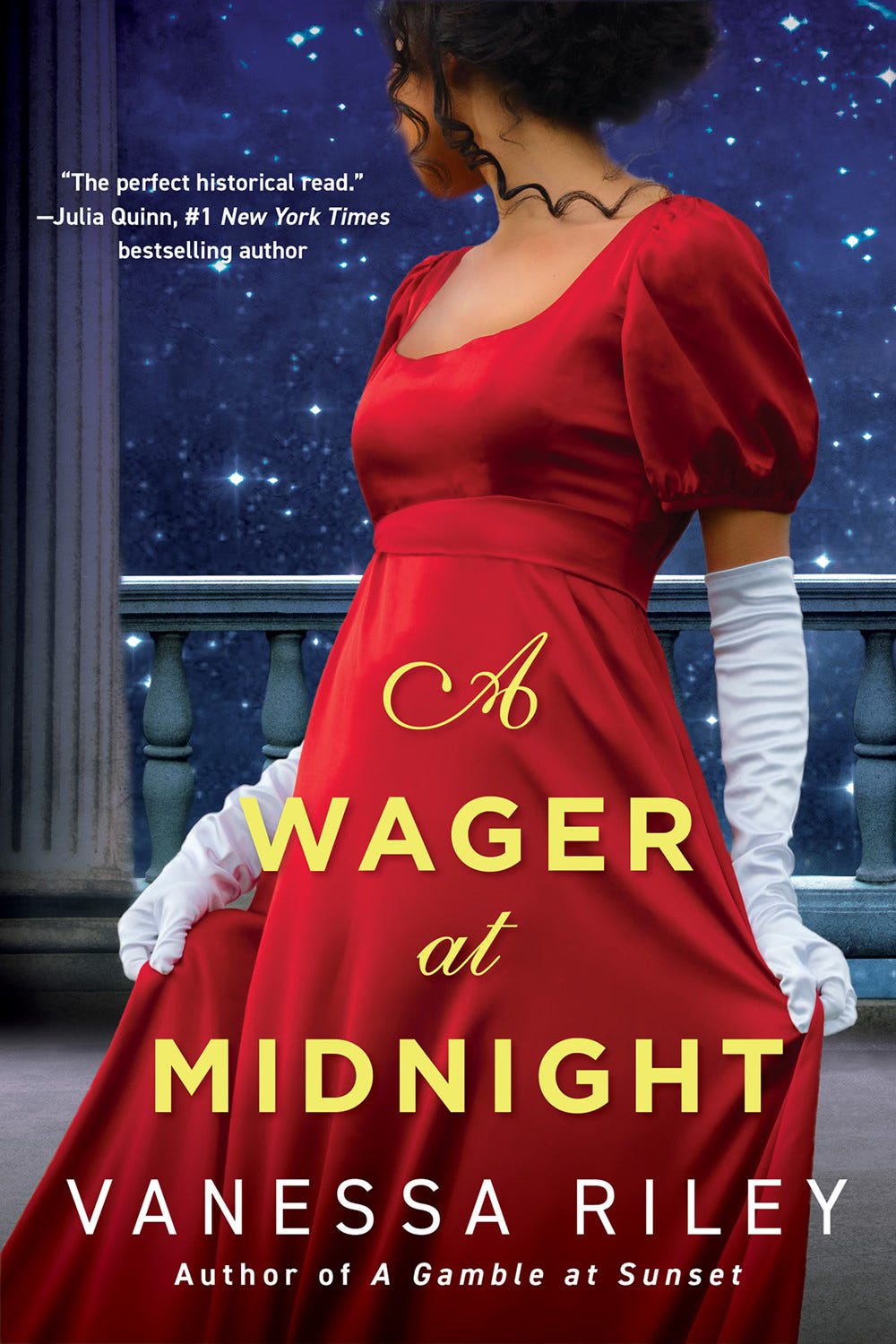

That moment had to change. I deleted the kiss. The scene in A Wager at Midnight is still funny, still scandalous, but it’s respectful. Some may say, “Vanessa, lighten up—it’s humor! And don’t we need more joy in the world?” All true. But here’s a greater truth: consent is not a double standard. It’s a rule. It’s a right. Everyone’s "no" should carry the same weight we modern women demand for ourselves.

A Wager at Midnight releases March 25.

The ability to say no is sacred. To paraphrase Matthew 5:37, “All you need to say is Yes or No; anything beyond this comes from the devil.”

Many of you might be nodding in agreement. Yet this week reminds us that some people still struggle with a woman’s no—especially when that woman is Black.

This week, a spokesman for the office of Barack and Michelle Obama announced that Mrs. Obama would not attend the 2025 inauguration. Unlike her absence from President Carter’s funeral, which was attributed to a scheduling conflict, this was a clear, definitive, unexplained no.

Reactions have been predictable. Some applaud her for setting boundaries, acknowledging the toll of public life and the personal risks she and her family have endured. Others clutch their pearls, lamenting political norms—those quaint phrases that, bless their hearts, weren’t universally applied when it mattered most.

Meanwhile, my people—oh, you know who you are—created a delicious meme that summed it all up: If I send you Michelle’s picture, I’m not coming.

From: @jennmjacksonphd

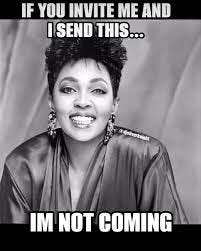

These memes reminded me of the ones sparked by Anita Baker when her concert, scheduled to start at 7 p.m. on May 11, 2024, at State Farm Arena in Atlanta, was canceled at 6:54 p.m. due to "unforeseen circumstances."

@sweet.alpha.lady from TikTok

I’ll admit, these memes are funny. But looking at the popularity of these memes reveals something sobering: Are women the only ones who cancel? Why aren’t there memes like these for men who say no? Do they not have the agency to do so?

Of course, that’s sarcasm—because men cancel all the time. They just aren’t mocked as much.

Chris Rock, for instance, canceled hosting the 2022 Governor’s Award after his infamous Oscar slap. If humor is fair game, where’s the meme with his picture saying, “Naw. Sorry I can’t be there. Still recovering from saying the wrong thing.”

Or take James Franco, who “mentally didn’t show up” to co-host the 2011 Oscars. Sure, he was physically present, but he failed to fulfill his duties. Anne Hathaway, the other co-host, had to carry the night. A woman having to pick up the slack? That sounds familiar—and is definitely meme-worthy.

Nonetheless, people have a right to cancel, just as they have a right to say no. That includes celebrities. Saying no should be a human right. But for that to hold true, society must first recognize the humanity and autonomy of every person who withdraws their consent.

Historically, women have struggled with autonomy and consent. For much of US history, women were required to live under the authority of a father, husband, or male guardian. It wasn’t until 1974 that women were allowed to obtain credit cards in their own name. Equal pay legislation dates back only to the 1960s. The societal acknowledgment of a woman’s right to make her way in the world is lacking. It’s hard to understand that a woman’s ability to work for fair wages and to decide her own path is merely sixty-five years old. That’s not that old. It’s barely able to get social security.

Alas, the history is bleaker for Black women. For us, the ability to say no to the most egregious violations was often denied. Our consent was stolen by laws, society, and systems meant to promote and protect others.

A Timeline of Black Women and the Right to Say No

1662: Virginia Hereditary Slave Law

Children’s status (enslaved or free) followed their mother, stripping Black women of autonomy over their offspring. Sidenote: This came about because Elizabeth Key, born to an enslaved woman and a white Englishman, Thomas Key, legally gained her freedom in 1655 by arguing that she was baptized and freed by her father. The 1662 law was enacted to ensure such cases could never happen again.

1705: Virginia Slave Codes

These codes reduced enslaved people to property. This codifies sexual violence against all enslaved but particularly Black women.

1786: Tignon Laws (Louisiana)

Black women were forced to cover their hair in public, erasing their self-expression and identity.

1857: Dred Scott v. Sandford

This decision denied Black people citizenship. This reaffirms that Black men and women are without legal rights to refuse exploitation or violence, nationwide.

1865–1866: Black Codes

Restrictive laws curtailed freedwomen’s mobility and punished those who refused exploitative labor with vagrancy charges.

1927: Buck v. Bell

This Supreme Court decision upheld forced sterilization laws targeting Black women under eugenics programs.

1944: The Rape Case of Recy Taylor

Recy Taylor identified her six white attackers, but they were never brought to justice. Alabama apologized only in 2011.

1980s: Workplace Dress Codes

Bans on natural hairstyles like braids and afros forced Black women to conform to Eurocentric beauty standards.

1994: Violence Against Women Act (VAWA)

While a step forward, this legislation didn’t fully address the unique barriers Black women face in seeking protection such as underreporting, racial profiling, mistrust in authority, and Access to Culturally Competent Services.

Of course there are some wins.

1967: Loving v. Virginia

This landmark case struck down laws eliminating restrictions on who women could marry.

1973: Relf v. Weinberger

This case exposed federally funded forced sterilizations of Black women, helping to end the practice.

2019–Present: The CROWN Act

This legislation prohibits discrimination based on natural hairstyles, affirming Black women’s autonomy over their appearance.

So, parity with others—being legally able to say yes to bodily autonomy and hairstyles—is less than a decade old for Black women. That should horrify you.

As a Black woman and a lover of history, I’m often told to forgive and forget—and there’s a heavy emphasis on forgiveness and a whole lot of forgetting. That notion is anathema to my soul. My lungs struggle to seize air under the weight of ongoing restrictions. There are new laws stripping away hard-fought rights. Fear and foolishness is trying to make hard-won victories DEI casualties. It’s book bans, whitewashed textbooks, tone policing, and countless microaggressions designed to smother.

Breathe.

Hear my heart: autonomy for me doesn’t mean taking from you. Equality for one group doesn’t mean making any other lesser. Checking on my sista doesn’t mean I wish ill on others—or the misters. We all gain when everyone’s yes and no are respected.

Writers, readers, citizens, hear me. Let us be wise with our words, speaking peace into existence. Let us remember and listen. Let us accept that no is a complete sentence, without the need for adjectives or explanations.

In times such as these when injustice still reigns, people have the right to step back, breathe, and find their peace.

Writers, I encourage you to take a more critical eye to your work. Let’s not ignore the forces trying to strip away consent—through laws, norms, even memes disguised as humor. We wield power with our words, and we should all consent to building up and renewing everyone who reads them.

If you want a deeper dive into the intersectionality of it all, as a book girly I have some recommendations for you:

Women, Race & Class by Angela Y. Davis explores the historical struggles of women, especially Black women, to claim autonomy and say no to oppression.

They Were Her Property by Stephanie E. Jones-Rogers, examines the role of white women in the American slave economy and highlights the systemic oppression of Black women.

Take My Hand by Dolen Perkins-Valdez, provides important connections between her novel and the case of Relf v. Weinberger and forced sterilizations.

Sister Citizen by Melissa V. Harris-Perry, analyzes how stereotypes affect Black women’s lives and their ability to assert agency.

Ain’t I a Woman? by bell hooks explores the intersections of race and gender and the marginalization of Black women.

Hood Feminism: Notes from the Women That a Movement Forgot by Mikki Kendall, highlights the importance of boundaries and self-advocacy, especially for marginalized communities.

Thank you for listening. Hopefully you’ll come again. This is Vanessa Riley.

Share this post