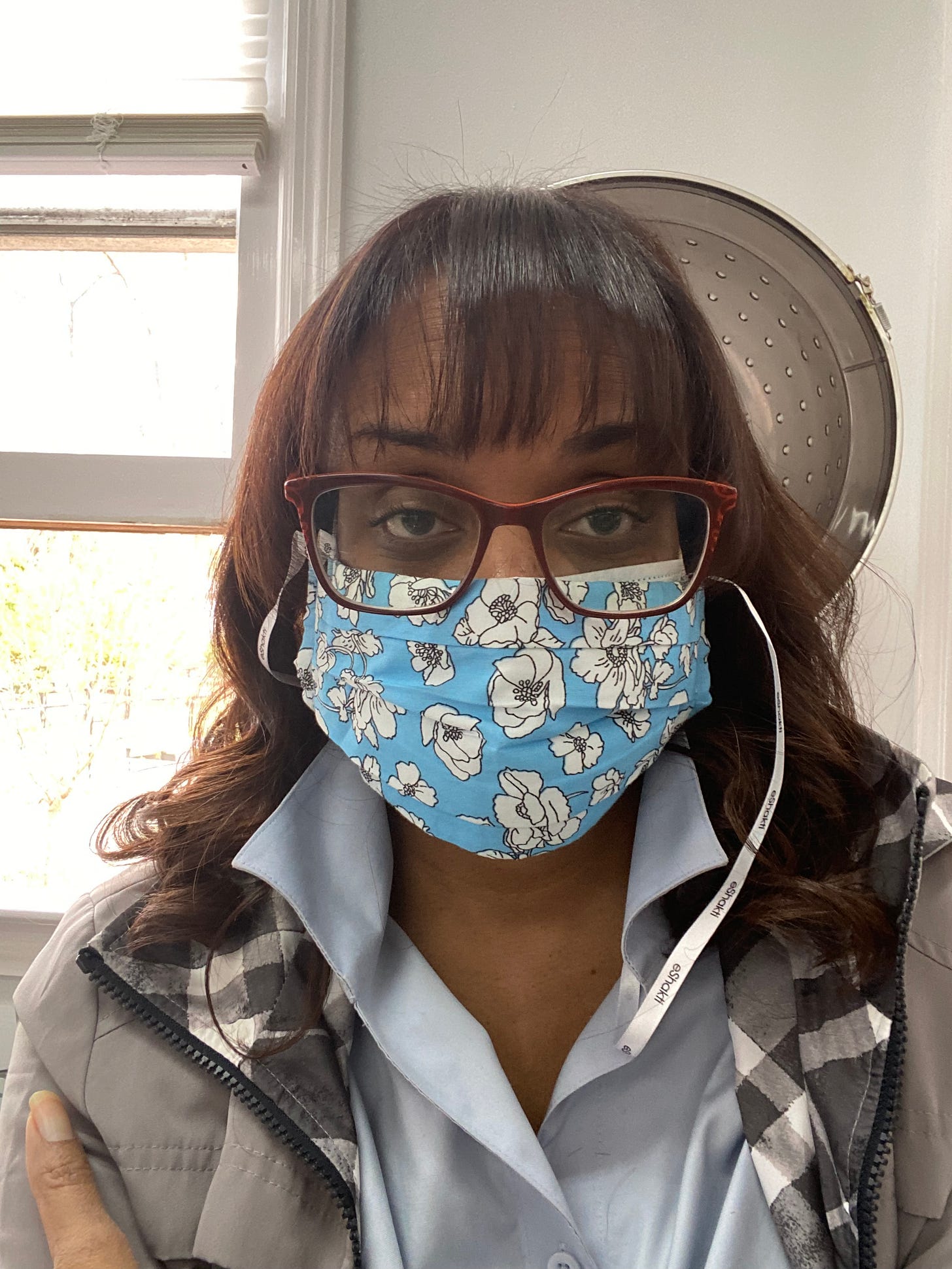

n 2020, America and the world were spiraling. COVID. COVID shutdowns, high COVID deaths, and the divisive uproar over wearing masks frayed nerves and divided communities. Then, in the middle of the chaos, we witnessed the killing of a man.

George Floyd, a man who’d run afoul of the law in the past, was approached by police under the false suspicion of using a counterfeit $20 bill.

At 8:20 p.m. on May 25, 2020, outside Cup Foods in Minneapolis, Officers Tou Thao, J. Alexander Kueng, and Thomas Lane encountered George. Kueng and Lane approached first, with blue lights twirling—maybe even a siren. George was visibly distressed and repeatedly said, “Please don’t shoot me,” referencing past traumatic experiences with the police.

At 8:21, officers attempted to place him in a squad car. George, unwisely, resisted, expressing intense anxiety and claustrophobia. “I’m not a bad guy… I’m scared, man,” he said.

By 8:25, Officer Derek Chauvin arrived. George was dragged out of the squad car and forced to the ground. Chauvin then placed his knee on George’s neck.

George was already handcuffed. Already on the ground. Already submissive. But Chauvin kept his knee there, applying his full weight to George’s neck.

Kneeling is supposed to be an act of humility—of reverence, of supplication, a gesture one might use to beg God for mercy.

But Chauvin wasn’t begging God. No, it was George who begged for his life. He cried out in search of humanity—for his humanity. He said more than 20 times: “I can’t breathe.”

Still, Chauvin didn’t move. George then cried out for his mother: “Mama, I’m about to die.”

A grown man, pleading for a breath, for his mother. Yet Chauvin kept kneeling, confident that no one would care about this Black man. To some, a man with a record deserves no second chance. So Chauvin kept kneeling, submitting not to justice but to cruelty—for 9 minutes and 29 seconds—until George Floyd died.

This moment shattered the stillness of a world already shaken. For a brief period, it seemed like nearly everyone agreed: This was wrong. This was murder.

I vividly remember the black squares on Instagram. The companies racing to fire employees who lied on peaceful protestors or weaponized stereotypes to suggest somehow George deserved this.

Companies finally acknowledged what many of us had known for years: that they had a diversity and inclusion problem. They made promises.

Penguin Random House pledged to increase diverse representation in its workforce and publish more books by Black authors and authors of color.

HarperCollins promised to amplify underrepresented voices in acquisitions, create fellowships, and increase donations to racial justice causes.

Simon & Schuster announced a new imprint for social justice and pledged to acquire more BIPOC authors. They donated to We Need Diverse Books and Black Lives Matter.

Macmillan acknowledged the lack of representation in its publishing and staff. They committed to more inclusive hiring, employee training, and outreach to BIPOC writers.

Hachette created a Diversity & Inclusion Council and mentorship programs for BIPOC employees. They donated to civil rights organizations and promised to publish more Black and Brown voices.

It wasn’t just publishing jumping to be counted in the righteous number. Target, Microsoft, Apple—major corporations pledged millions to diversity initiatives and underserved communities.

But here we are, just five years later.

Reports from The Washington Post, Reuters, and business analysts show a corporate backslide. Hachette has made notable progress in BIPOC hiring and acquisitions. But others—Penguin Random House, HarperCollins, Simon & Schuster, and Macmillan—have not provided updated public reports on their commitments. There’s a lack of transparency.

And when BIPOC authors speak up about their experiences with these opaque publishers—about the lack of marketing, the minimal support at launch, the inadequate investments in advertisements—it becomes clear that many of those 2020 commitments were performative. Empty, breathless gestures.

The biggest offender? We all know—Target. After loudly promoting their DEI programs, they rolled them back—loudly and publicly. And sales have significantly declined. I doubt they’ll ever fully regain the trust of the loyal customers they betrayed.

There’s been talk that Target’s retreat has caused some Black authors to miss major bestseller lists. That’s not the full story. The truth is: momentum makes the difference. Local bookstore buys matter count just as much—often more.

Don’t get me wrong—I love walking into a big store and seeing my book face-out on the shelf. I’m deeply grateful to every bookseller, clerk, and sales rep who’s done that for any of my titles.

But let’s be honest: many Black and BIPOC authors lack consistent support from publishers. A publisher can create magic. They can generate momentum—or they can smother it. And I’ve wondered, more than once, if some of these acquisitions with no follow-through are just another version of the black Instagram squares. A performance. “Look, Mama—we did something.” But then the cover’s bad, the e-book or audio launch is botched, and the book disappears, drowning in wrong or limited search results.

So I ask: Did some publishers in 2020 merely shift their knee slightly off the necks of Black writers—just enough to say they weren’t actively killing careers?

George Floyd didn’t deserve to die. He was a man. A father. A person with a past—but one who had a future, until it was stolen.

I use George’s first name throughout this essay because this is personal. I want you to remember how it felt. You saw the video. As a Black woman, that could have been my husband. One of my brothers, my uncles, or my beloved nephews.

I’m not going to lie—my heart still races when I see flashing blue lights. I don’t want to be Sandra Bland. Or Breonna Taylor. I have books to write, stories to tell, a family that I need to be here for. Yet, unless you sit beside me, you’ll never hear the sound I make—the soft, involuntary gasp of relief—when a patrol car passes and doesn’t pull me over.

That breath I’ve been holding finally escapes. And in that moment, I relearn how to breathe.

Books to help us process what happened and where we find ourselves:

His Name Is George Floyd by Robert Samuels & Toluse Olorunnipa is the Pulitzer Prize-winning biography that details Floyd’s life and the systemic racism that shaped it.

Why Are All the Black Kids Sitting Together in the Cafeteria? by Beverly Daniel Tatum - Examines racial identity development and institutional bias, including in schools and publishing.

Well-Read Black Girl edited by Glory Edim - Celebrates Black women writers and the importance of being seen in literature.

Help me build momentum for Fire Sword and Sea—spread the word and preorder this disruptive narrative about female pirates in the 1600s. This sweeping saga releases January 13, 2026.

Show notes include a list of the books mentioned in this broadcast. This week, I'm highlighting The Dock Bookshop through their website and Bookshop.org

You can find my notes on Substack or on my website, VanessaRiley.com under the podcast link in the About tab.

If you believe like me that stories matter—tap like, share with a friend, and hit subscribe to Write of Passage.

Thank you for listening. Hopefully, you’ll come again. This is Vanessa Riley.

Share this post