What does the word "diverse" mean to you when you see it in relation to books and publishing? For some, it is joy. It means being seen. It's a celebration. For others, it is a tag to "otherize" and foment hate. In publishing, it means a journey fraught with both peril and joy. Today, I’m going to give you a state of affairs. In true fashion, I will present the history of diverse publishing in the U.S., work through some of the issues, and then invite you to be a part of the conversation.

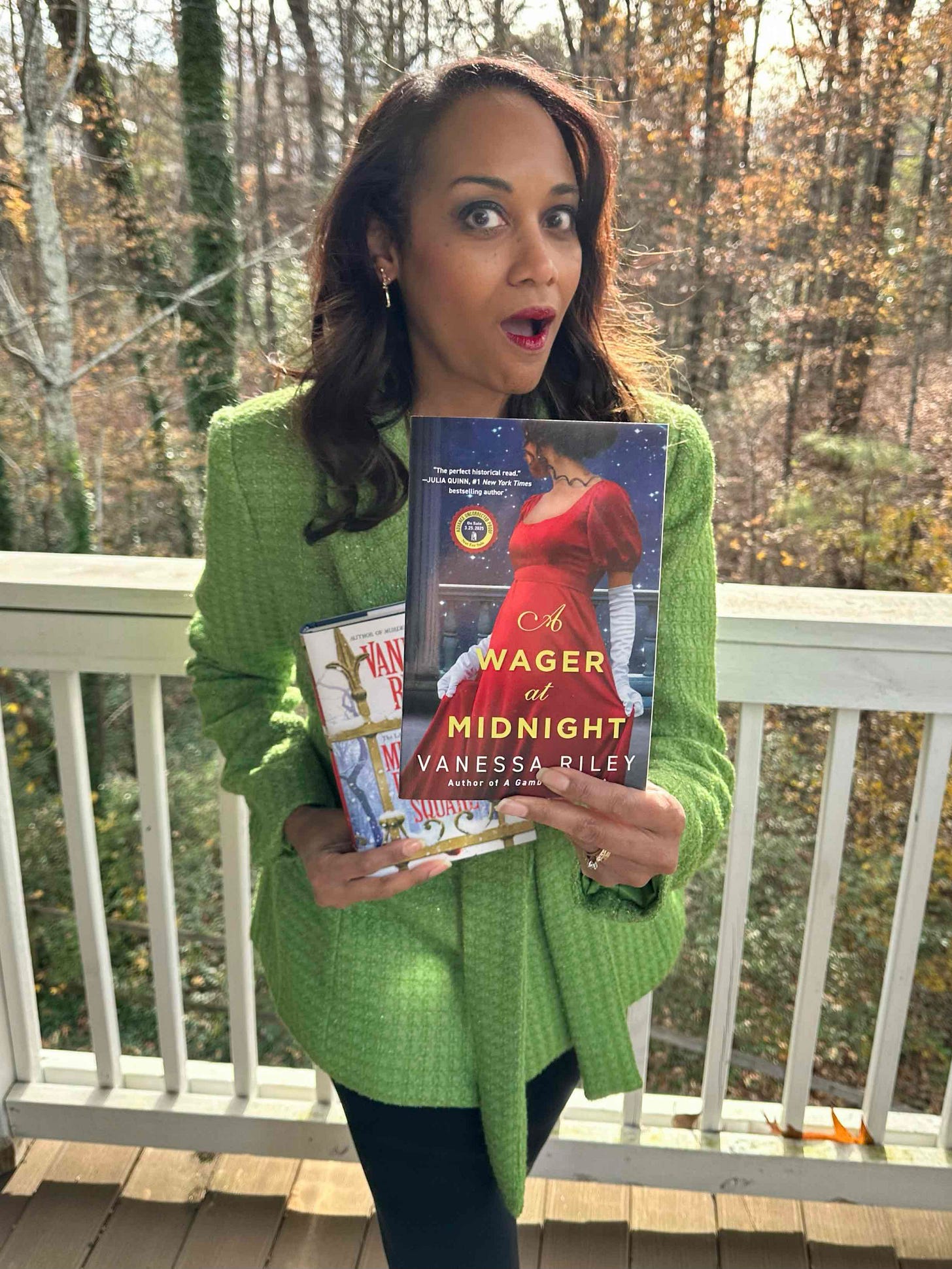

Vanessa Riley standing on her porch being diverse, holding two genres: mystery and romance… with Black people.

Let’s Unpack the Word Itself

"Diverse" is often used in publishing as shorthand for books that feature nonwhite characters, non-Western settings, LGBTQ+ protagonists, or disabled representation. But here’s the thing: diverse only exists in contrast to what’s considered "normal"—a category still largely defined by whiteness, heterosexuality, and able-bodiedness.

The term can unintentionally center whiteness as the default, as seen in publishing practices where diverse books are often marketed as niche or special interest, rather than universal. For example, promotional materials might highlight the diversity of a story as its primary selling point, rather than focusing on its universal themes or compelling narrative, subtly reinforcing the notion that these stories are "different." Similarly, books featuring nonwhite protagonists are frequently segregated into separate categories, making them less visible to mainstream audiences. When someone says, “This book is so diverse,” what they’re often implying is, “This book is not about the kind of people or places I usually read about.” And if the word diverse causes discomfort, it’s worth asking why. What is it about encountering other perspectives that feels threatening, or so unfamiliar it warrants a disclaimer?

A Timeline of Diverse Movements in Publishing

The truth is, the push for diverse stories is nothing new. Starting as early as 1965, one can track the movement or small earthquakes that have changed the publishing industry:

1965: Formation of the Council on Interracial Books for Children, challenging racist stereotypes in children’s literature and advocating for inclusive stories.

1969: Launch of the Coretta Scott King Book Awards, recognizing outstanding African American authors and illustrators.

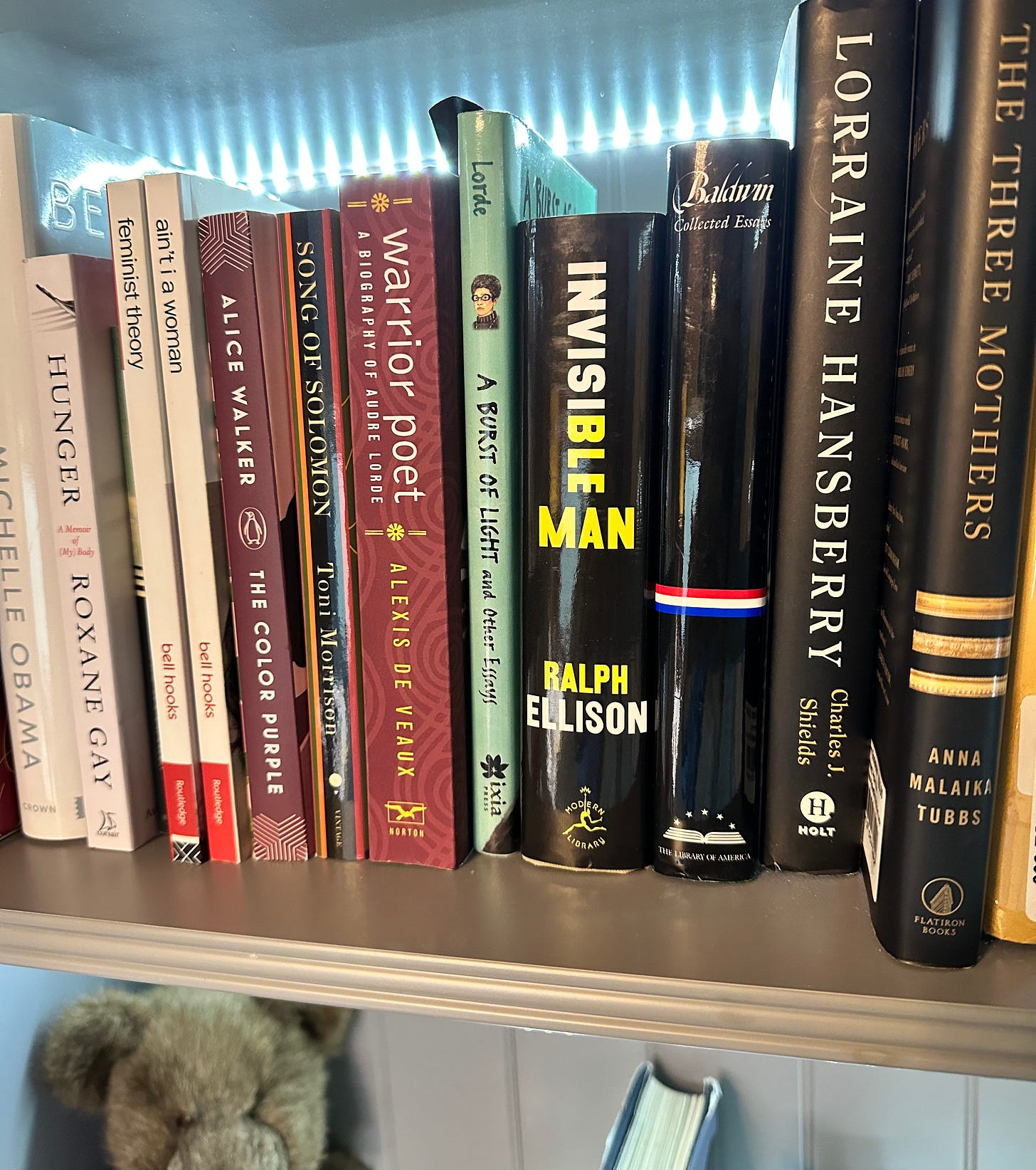

1975–1990s: A handful of authors break through (or are allowed to breakthrough), leaving a lasting impact on readers:

James Baldwin - The Devil Finds Work (1976)

Mildred D. Taylor - Roll of Thunder, Hear My Cry (1976)

Toni Morrison - Song of Solomon (1977)

Maya Angelou - And Still I Rise (1978)

Octavia E. Butler - Kindred (1979)

Lucille Clifton - Two-Headed Woman (1980)

Audre Lorde - The Cancer Journals (1980)

bell hooks - Ain’t I a Woman? (1981)

Angela Davis - Women, Race, & Class (1981)

Alice Walker - The Color Purple (1982)

Gloria Naylor - The Women of Brewster Place (1982)

August Wilson - Fences (1985)

Virginia Hamilton - The People Could Fly (1985)

Rita Dove - Thomas and Beulah (1986)

Walter Mosley - Devil in a Blue Dress (1990)

Terry McMillan - Waiting to Exhale (1992)

Eva Rutland - The House Party (1991)

Beverly Jenkins - Night Song (1994)

Brenda Jackson - Tonight and Forever (1995)

One of my beloved bookshelves.

2000s: The #WeNeedDiverseBooks movement emerges, pushing publishers to examine their rosters. The next remnant of influential writers and works come to the forefront of publishing:

Edwidge Danticat - The Dew Breaker (2004)

Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie - Half of a Yellow Sun (2006)

Toni Morrison - A Mercy (2008)

Jesmyn Ward - Salvage the Bones (2011)

Marlon James - A Brief History of Seven Killings (2014)

Ta-Nehisi Coates -- Between the World and Me (2015)

Colson Whitehead - The Underground Railroad (2016)

Roxane Gay (

) - Hunger (2017)Angie Thomas - The Hate U Give (2017)

Michelle Obama - Becoming (2018)

Ibram X. Kendi - How to Be an Antiracist (2019)

Brit Bennett - The Vanishing Half (2020)

2018: The Cooperative Children’s Book Center reports that books by or about Black, Indigenous, and People of Color make up only 10% of published books. (This has improved but remains a concern.)

2020: The murder of George Floyd spurs demand for anti-racism literature. Publishers pledge to diversify catalogs and increase representation in leadership. The #PublishingPaidMe movement highlights disparities in compensation for BIPOC authors.

Present Day

Initiatives like Blackout Bestsellers Week have faded, with sales and visibility campaigns showing diminishing participation. On June 25, 2025, Publishers Weekly headlined: "Layoffs Hit Little, Brown Editorial; Tracy Sherrod, More Depart." The article states: "With the departure of Sherrod, the trade publishing industry has now seen three high-profile Black women depart from top positions since the big publishers made a public commitment to increase their diversity, equity, and inclusion efforts in the wake of the 2020 murder of George Floyd. Lisa Lucas was dismissed from Pantheon Schocken last month after three years at the imprint, while Dana Canedy left her role as SVP and publisher of the Simon & Schuster imprint in 2022, after two years."

In August, the New York Times followed up with, "‘A Lot of Us Are Gone’: How the Push to Diversify Publishing Fell Short." It detailed a system that allows trailblazers to become fatigued, new entrants discouraged, and emphasized the emotional toll of continuously advocating for inclusion in a resistant system.

Why This Matters to Me

Critics argue that many efforts remain performative. A lot of discourse feels performative. I remember a widely circulated screed on illustrated covers, advocating for photography instead. I sat there, quietly eating my lunch, knowing my most widely circulated and bought romance books are with illustrated covers—like A Duke, The Lady, and A Baby. Its sales dwarf my photorealistic covers, which showcase beautiful Black characters instead of race-ambiguous caricatures.

The trade cover of A Duke, The Lady, and A Baby.

I, a Black female writing disruptive stories about the true history of Black women and women of color—of Black folks finding love and dignity within systems that discourage anything but conformity—sometimes feel lost. A recent comment on my 2025 historical romance, A Wager at Midnight, read: “Love the diverse characters in this book. It doesn’t take away the romance or the fun. It actually enriches the romance.”

Say What?

I want to make something clear: reviewing is hard. Putting your thoughts out there, especially in today’s fraught cultural climate, takes guts. I have no intention of criticizing this reviewer personally. In fact, maybe they’re doing a service by signaling to nervous readers that diverse stories won’t accidentally make them "woke."

A reader made a Funko Pop of Scarlet from a Wager at Midnight. That’s a reader's excitement for the story.

But comments like these invite a larger conversation about how we perceive books by and about people who exist outside of the dominant narrative. While I deeply appreciate the kind words, the phrasing raises questions: Do readers, particularly white readers, still need reassurance that stories with diverse characters are "safe" to enjoy? Is the word diverse itself triggering? Does it bring hesitation?

Literature is one of the safest ways to explore unfamiliar perspectives. It costs nothing to empathize with characters who look different from you. In fact, it enriches you. Diverse or diversity shouldn't trigger you. Ask why it does.

Moving Forward

Below are my personal thoughts on how we can reach a point where any book can excite any reader without clauses or pauses:

Books by authors of color should be marketed as universal stories.

Readers should challenge themselves to read widely all year, not just in February.

Reviewers should recognize that their willingness to review, as well as the words they use, are invaluable in shaping narratives about what stories matter.

And if you want to read a “diverse” romance, check out A Wager at Midnight. I promise it’s a terrific read, full stop.

Be A Part of the Conversation

Add your comments and share your experiences. Authors, feel free to contribute your insights as well. I’ve posted a poll on Spotify to explore where readers stand. There’s no judgment—having open discussions is key to moving forward.

This is Vanessa. I’m looking forward to hearing from you!

Share this post