Kendrick Lamar’s Super Bowl LIX halftime performance during the game between the Kansas City Chiefs and the Philadelphia Eagles has set the internet—and much of the world—abuzz. Nineteen Minutes by Jodi Picoult is the most banned book in America for challenging the way people see the world. I’m sure those same folks will be coming for Kendrick’s thirteen minutes for challenging the way the world operates.

Less than a week later, scholars, pontificators and fools offered hot takes, deep dives, and debates about every minute of the performance. Those versed in Black scholarship loved it. Others criticized it. And, there were plenty of opinions and outright lies circulating. But here’s what’s undeniable: 133.5 million people watched the halftime show at Caesars Superdome, making it the most-watched in Super Bowl history. According to Roc Nation, Apple Music and the NFL, this number beats those who watched the Fox broadcast of the game which averaged 126 Million viewers. That 7.5 million more tuning into halftime than game time.

Context is King: History of the Halftime Show

Let’s talk about origins. The Super Bowl, the annual championship game of the NFL, has been played since 1967, with college marching bands providing halftime entertainment.

Grambling State University, a HBCU had its marching band perform at Super Bowl II (1968).

In 1972, the first halftime show featuring a Black performer, non-marching band member, was Ella Fitzgerald at Super Bowl VI in Miami where she sang Mack the Knife.

Super Bowl IX (1975) in New Orleans paid tribute to Duke Ellington with Grambling State’s Marching Band and the Mercer Ellington Orchestra.

When was the next Black moment? We have to skip a bunch of years to get to 1991, Super Bowl XXV where the incomparable Whitney Houston delivered a stirring rendition of The Star-Spangled Banner, but she wasn’t the halftime headliner—New Kids on the Block were. In 1993, Michael Jackson, the 1st Black performer to headline the halftime show dazzles the crowds at Super Bowl XXVII (27) and sets the standard for pop stars and the future of football’s biggest event. The King of Pop owned the stage and every moment of his performance. If 100,000 people had actually turned off their TVs like they claimed they did, Michael Jackson would still hold the record, with an audience of 133.4 million viewers.

Other notable performances featuring Black artists across the lengthy history of halftime shows include:

• Super Bowl XXII (22nd, 1988) – Chubby Checker appears with the Rockettes and 88 grand piano players.

• Super Bowl XXIX (29th, 1995) – Patti LaBelle & Teddy Pendergrass were featured along with Tony Bennett.

• Super Bowl XXX (30th, 1996) – Diana Ross dazzled in a red gown and even changed outfits mid-show.

• Super Bowl XXXI (31st, 1997) – A blend of James Brown appearing with ZZ Top and The Blues Brothers Band.

• Super Bowl XXXII (32nd, 1998) – A Motown tribute featured The Temptations, Smokey Robinson, Martha Reeves & The Vandellas, Queen Latifah, and Boyz II Men. Watching those young men of Boyz II Men sing about their mothers hits differently now, especially juxtaposed with Lamar’s solitary silhouette atop the GNX in New Orleans and his dancers, young men gathered under a street lamp.

• Super Bowl XXXIII (33rd, 1999) – Stevie Wonder joins Gloria Estefan and Big Bad Voodoo Daddy.

• Super Bowl XXXIV (34th, 2000) – Toni Braxton is featured.

• Super Bowl XXXV (35th, 2001) – Featured Mary J. Blige and Nelly.

• Super Bowl XXXVIII (38th, 2004) – Janet Jackson’s infamous "wardrobe malfunction” occurred.

• Super Bowl XLI (41st, 2007) – Prince performed in the rain, delivering one of the most iconic halftime shows in history.

• Super Bowl XLV (45th, 2011) – Usher and the Prairie View A&M University Marching Storm supported The Black Eyed Peas.

• Super Bowl XLVI (46th, 2012) – Madonna headlined with Nicki Minaj and CeeLo Green at Lucas Oil Stadium.

• Super Bowl XLVII (47th, 2013) – Beyoncé tore down the Superdome in New Orleans, reuniting with Destiny’s Child.

• Super Bowl 50 (2016) – Beyoncé returned, performing a Black Panther-inspired set supporting headliner Coldplay.

• Super Bowl LIII (53rd, 2019) – Big Boi and Travis Scott performed in Atlanta.

• Super Bowl LV (55th, 2021) – The Weeknd headlined in Tampa.

• Super Bowl LVI (56th, 2022) – Dr. Dre, Snoop Dogg, Kendrick Lamar, Mary J. Blige, and 50 Cent rocked SoFi Stadium in Inglewood.

• Super Bowl LVII (57th, 2023) – Rihanna, pregnant and powerful, delivered her first live show in over five years.

• Super Bowl LVIII (58th, 2024) – Usher commanded the stage in Las Vegas.

• Super Bowl LIX (59th, 2025) – Kendrick Lamar featuring SZA.

So, let’s be clear: Black performers at the Super Bowl are not new. Hip-hop and rap at the Super Bowl are not new. For those suddenly enraged—why weren’t you bothered during the 39 other years when Black artists weren’t featured or headlined? The selection process has always been based on merit—the most talented for the job, period. Right?

And with DEI (diversity, equity, and inclusion) now the new taboo, let me ask: Why do some get upset when things aren’t diverse—when people who look like them aren’t centered or given an extra slot or quota on stage? Do you want equity and inclusion or not?

Kendrick Lamar is highly qualified. He won the 2018 Pulitzer Prize in Music for his album DAMN. He’s a 27-time Grammy winner, and one cannot deny that his 2024 diss track, Not Like Us, has the world on fire. Please, show me someone with better credentials who’s willing to perform a 13-minute Super Bowl halftime show—for free.

Let’s Dive into the Performance

Lights flash. I see nine squares and glowing X’s and O’s. I wonder—are we about to get Tic-Tac-Toe or something else? In the background, a power bar, formed of stadium lights or drones, begins to load. I know we’re about to witness something special.

More lights flash. The bar is almost at 100%, and I sit on the edge of my seat, expecting a high level of storytelling artistry from Lamar. According to Britannica, art is a visual object or experience consciously created through an expression of skill or imagination—and right now, skill and imagination are exactly what we need.

In a flash, a "Start Here" sign and arrow appear, pointing to the lone figure on the hood of a Buick GNX. Kendrick Lamar, a young Black man, crouches on the car. The image evokes loneliness—it’s dramatic, and I’m locked in as the gleaming black Buick GNX (Grand National Experimental) transforms into a clown car, packed with dancers spilling out. So many exit the vehicle that I later learn the seating had to be removed to fit them all into that tight, cramped space—not unlike bodies crammed into the hulls of ships.

On Instagram, Lamar writes about authenticity: "In the moment of confusion, the best thing you can do is find a GNX. Make you realize the only thing that matters in life is that original paperwork. That TL2 code. 1 of 547."

What does original paperwork mean when you’re the descendant of chattel slavery? Is it the slave ship’s manifest that documented the theft of ancestors? The bill of sale from massas in the States or Grand Blancs in the Caribbean, depending on where your roots were auctioned off? Or is it the manumission papers, declaring your freedom—bought at a price?

This leads me down another rabbit hole: authenticity—who is American and who is not? In a country that often forgets to be kind to the foreigner (Leviticus 19:33-34), or that it was founded by immigrants—many seeking religious freedom, a fresh economic start, or escape from oppression—this question cuts deep. It’s a scar that never fully heals.

Did you know that, in the past—like I wrote about in Island Queen—people with any tint to their skin have had to carry manumission papers or proof of their free status to avoid being accosted? Many around the nation feel this burden now. We’re still caught in this cycle because we’ve banned the books that teach history and empathy.

Back to Football—America’s Game

I highly recommend reading Moving the Chains: The Civil Rights Protest That Saved the Saints and Transformed New Orleans by Erin Grayson Sapp, which examines the 1965 AFL All-Star Game boycott, where players protested against racial discrimination in New Orleans.

Another must-read is Race and Football in America: The Life and Legacy of George Taliaferro by Dawn Knight, chronicling the journey of George Taliaferro, the first African American drafted by an NFL team, and the challenges he faced.

Red, White, & Blues of Uncle Sam

The visuals cut to Uncle Sam—portrayed by Academy Honorary Award winner Samuel L. Jackson. With a film career grossing over $27 billion worldwide, making him the highest-grossing actor of all time, Jackson embodies this iconic American figure. Some might be wondering, What in the DEI is going on with this Black version of a fictional Americana, but it soon becomes clear: Uncle Sam is here to keep Lamar in line.

Jackson plays Uncle Sam as Uncle Tom. Uncle Tom’s Cabin, Harriet Beecher Stowe’s 1852 abolitionist novel, portrayed White men as morally bankrupt and Black individuals as either complicit in oppression or suffering under it. The book also depicted White women as the moral conscience of a system they benefited from, yet remained angelic through their Christian preaching. The novel ends with the enslaved Tom dying because he refuses to betray two Black women who have escaped. As he dies, he forgives his abusers.

The novel’s humane portrayal of enslaved people and its righteous female characters were said to have contributed to the start of the Civil War. Enraged Southerners banned the book. In the 1940s, Langston Hughes attempted to revive interest in it, but Richard Wright and James Baldwin criticized it, arguing that it promoted the image of an "Uncle Tom"—a Black person subservient to Whites or complicit in oppression.

In Lamar’s performance, Uncle Sam enforces the “party line” of American success. At times, he antagonizes Lamar, telling him, “You’re too loud, too reckless, too ghetto.” He dictates that since Lamar refuse to comply with the rules of the American game, he must be penalized: “Deduct one life.”

The death count is brutal—and so is American history, even without including the countless lives lost under enslavement:

• Fort Pillow Massacre (1864): Confederate soldiers slaughtered surrendering African American Federal troops stationed at Fort Pillow, Tennessee. Between 277 and 295 Union troops were killed.

• Memphis Massacre (1866): A White mob murdered 46 African Americans, most of whom were Union veterans.

• New Orleans Massacre (1866): A White mob killed 35 Black citizens and wounded 100 for peacefully gathering in support of a political meeting.

• Colfax Massacre (1873): A White militia massacred approximately 150 African American militia members who were attempting to surrender in Colfax, Louisiana.

• Wilmington Massacre (1898): A premeditated attack left 60 Black Americans dead as White supremacists sought to eliminate African American participation in government and permanently disenfranchise Black citizens.

• Atlanta Race Riot (1906): White mobs killed at least 12 African Americans and burned over 1,000 homes and businesses in Black neighborhoods.

• Springfield Race Riot (1908): The Illinois state militia was called to quell the chaos as a White mob shot innocent people, burned homes, looted stores, and mutilated and lynched Black residents.

• Chicago Race Riot (1919): The “Red Summer” began when a Black youth was stoned to death for swimming in an area reserved for Whites. Over 13 days of lawlessness, 23 African Americans were killed, 537 were injured, and 1,000 Black families were left homeless.

• Ocoee Massacre (1920): A massacre of Black residents in Ocoee, Florida, left approximately 30 dead.

• Tulsa Race Massacre (1921): Tulsa’s prosperous Black neighborhood of Greenwood, known as Black Wall Street, was destroyed—1,400 homes and businesses burned, nearly 10,000 people left homeless. Vanessa Miller’s The Filling Station is a poignant portrayal of the massacre and the resilient rebuilding that followed.

The sacrifice of Black lives makes Lamar’s imagery of tangled bodies forming the flag raw. It hit me in the pit of my stomach. I live knowing that the sacrifices and body counts will continue to rise, forming trending hashtags: #BreonnaTaylor #AhmaudArbery #TamirRice #TrayvonMartin #GeorgeFloyd

The Movement of Dancers

The visuals of Black dancers dressed in red, white, and blue moving around what is now clearly the game receiver mirror how many of us are on the X button—saying yes to conforming, to getting along, to advancing, to avoiding having our dreams burned up by a jealous or misinformed mob. When the dancers near the circle stage—the reject button—they enter a staircase that leads to a slope, which brings them back to where they started. Is that a metaphor suggesting we are better off right where we began before chasing conformance?

The Most Misunderstood Part: Serena Williams

Serena Williams, who once dated Drake, danced the Crip Walk on stage. Distraught commentators ground their teeth, calling it disrespectful for a forty-year-old mother to be dancing on the figurative grave of her ex.

The caucasity of this is the belief that this exhibition was about a man or a former relationship. Serena Williams is not just some “baby mother.” She was ranked No. 1 in the world in women's singles by the Women's Tennis Association (WTA) for 319 weeks—the third-most of all time. Williams has won 73 WTA Tour-level singles titles, including 23 major women's singles titles. She is the only player to accomplish a career Golden Slam in both singles and doubles.

The Crip Walk is a celebration, notably adopted by her folks from her city of Compton, and it symbolizes the alliance of California street gangs, the Crips— as in Crips vs. Bloods. No, Serena is not part of a gang. But like the dance’s founder, Henry Crip—a Harlem dance legend who lost an arm and a leg in a car accident—she celebrates moving forward and achieving. Williams first did the Crip Walk in 2012 at Wimbledon, eliciting massive backlash for celebrating a huge win—for the girl from Compton.

Seeing her dance freely, hair flowing, I think of the Tignon Laws of New Orleans, which I mentioned in my podcast Consent in the Time When a Black Woman Can Say No, and the long history of policing Black women’s bodies. In Serena, I saw joy and celebration. If I am to think of Drake at all—a man who has used Serena’s name in diss songs—I see freedom from a toxic relationship. That’s cathartic.

Ok, Now the Hotep Or Too Deep to be Real Take

Lamar does say he is a stargazer, so maybe the 16 stars on Uncle Sam’s jacket resemble the Little Dipper. if I squint, I can see it. But the talk online about the design representing the 16 free states—states that prohibited slavery between 1850 and 1858—seems like a stretch. These arbitrary dates are supposedly tied to U.S. naval activities interrupting the slave trade.

I’m not buying this. The U.S. Navy's role against stopping transport began in 1820 when warships deployed off West Africa tried to catch American slave ships, but enforcement was sporadic until the Navy deployed a permanent African Squadron in 1842. Last time I checked, 1850 and 1842 are different years. A rounding error won’t make them the same.

By 1858, there were 32 states in the Union, including Minnesota, which was admitted on May 11, 1858. California was the 31st state, admitted on September 9, 1850. If I count the list of free states—states that prohibited slavery—I get 17:

1. Pennsylvania – December 12, 1787

2. New Jersey – December 18, 1787

3. Connecticut – January 9, 1788

4. Massachusetts – February 6, 1788

5. New Hampshire – June 21, 1788

6. New York – July 26, 1788

7. Rhode Island – May 29, 1790

8. Vermont – March 4, 1791

9. Ohio – March 1, 1803

10. Indiana – December 11, 1816

11. Illinois – December 3, 1818

12. Maine – March 15, 1820

13. Michigan – January 26, 1837

14. Iowa – December 28, 1846

15. Wisconsin – May 29, 1848

16. California – September 9, 1850

17. Minnesota – May 11, 1858

So the math and the facts aren’t jiving. Kendrick Lamar is very precise in his lyrics. An arbitrary number or pattern doesn’t seem to be his M.O. I could stretch and say he mentions losing 16 friends in his song “wacced out murals,” but then I’m just spitballing.

Not everything has a direct meaning, but that’s the beauty of art—it can mean many different things to different people. Kendrick Lamar and his performance is art and it should be applauded for making us all stop and think.

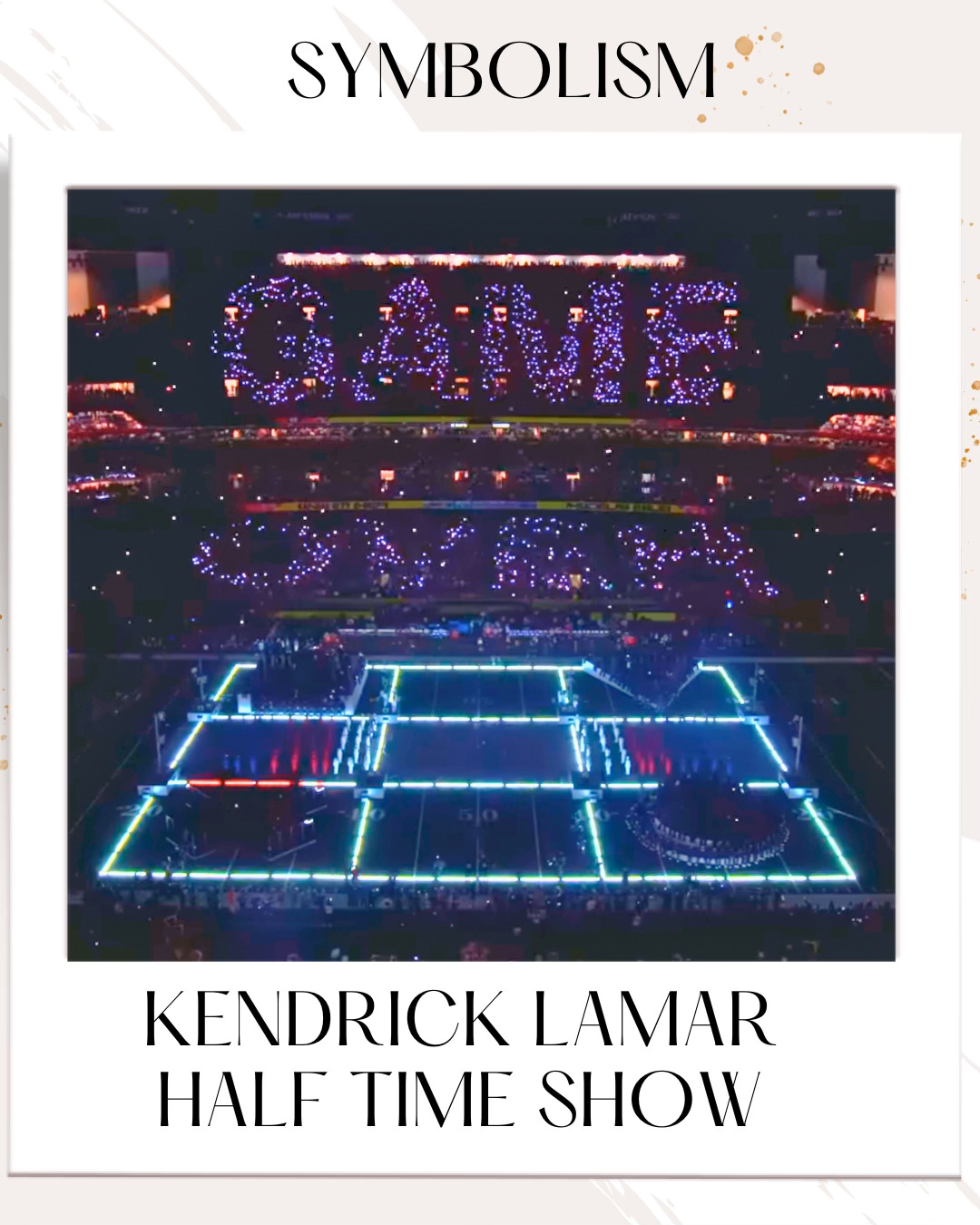

Ending the American Game

As the last notes of “Not Like Us” finishes, Lamar and company launch into “TV Off.” When he finishes the rap, he holds up a virtual remote, turns it off, and forces the stage to go dark. In lights, we see the sign: Game Over. Does he mean the American game is over because we refuse to learn from the past or that he’s stop playing the game? Lights out—Is that symbolic of a Revolution being televised until it’s not? Is the American Game going to stop feeding on Black life, Black culture, and Black breath? What happens if every American, turns off the TV, the cellphone, social media, etc. and stops playing the game?

America is founded with the God-given right to have differences of opinions. Of being able to choose your path, to dream the biggest dreams, and to make them happen—on or off the field. Whether we play the game or not, movement, not standing still, is how we inch forward toward the goal posts. It’s how we will awaken and form a more perfect union.

You can learn more about banned books from the American Library Association (ALA), PEN America, and Authors Against Book Bans.

Show notes include a list of books I’ve mentioned in the broadcast. This week, I’m spotlighting Brave and Kind Books through Bookshop.org.

Miller, Vanessa, (2025) The Filling Station. HarperCollins.

Picoult, Jodi. (2007). Nineteen Minutes. Atria Books.

Riley, Vanessa. (2021). Island Queen. William Morrow.

Hughes, Langston. (2000). Simple's Uncle Sam

Lamar, Kendrick. (2017). DAMN [Album]. Top Dawg Entertainment.

Lamar, Kendrick. (2024). GNX [Album]. Top Dawg Entertainment.

Sapp, E. G. (2019). Moving the Chains: The civil rights protest that saved the Saints and transformed New Orleans. Louisiana State University Press.

Smith, A. W., & Hailey, W. (2020). Race and Football in America: The life and legacy of George Taliaferro. Indiana University Press.

Stowe, Harriet Beecher. (1852) Uncle Tom's Cabin.

Images are screenshots of ROC Nation and Apple Music feeds.

Share this post